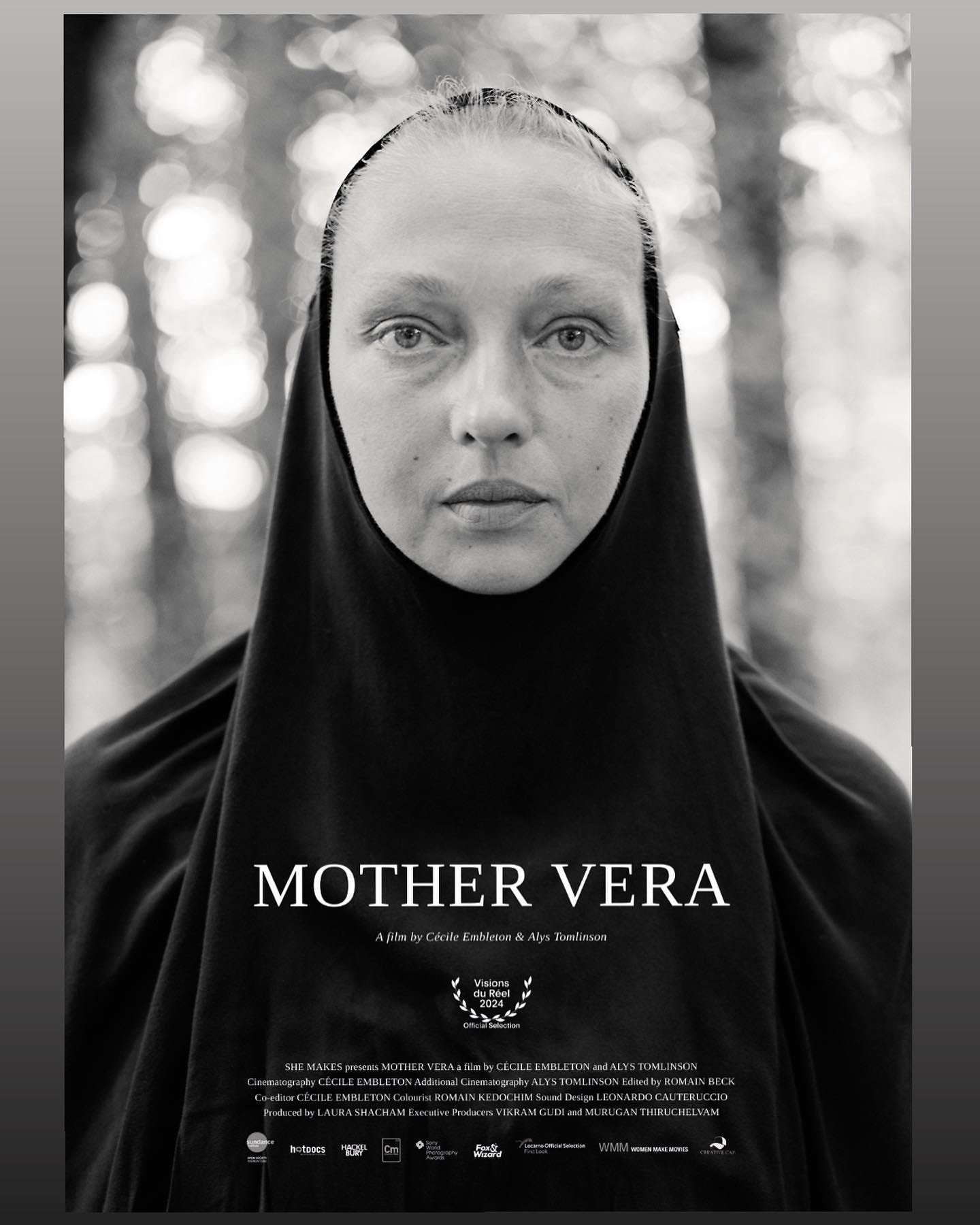

I spoke to director, cinematographer, and my good friend Cécile Embleton (instagram) about her new film Mother Vera, which is playing at the London Film Festival next month.

This is a feature documentary about the life of a young orthodox nun from Belarus.

I have seen it, and it is spectacular.

Cécile and I discuss literature, her influences, and the challenges and joys of making arthouse cinema.

I thought I’d have experiment with including the transcript of our conversation, lightly edited for readability.

Transcript

Cecile and Bryan 2024-08-29

Bryan: Hi Cécile.

Cécile: Hi Bryan.

Bryan: So you are Cécile Embleton, filmmaker. Would you like to introduce yourself?

Cécile: Yeah, sure. So, I am a documentary director. I live in London. I'm British French, and I, yeah, spend most of my life thus far, as an adult, trying to work out how to make an art house documentary alongside Making a living. Yes. So, yeah, that's kind of my main focus in life.

Bryan: And I have seen one of your films very recently and loved it.

That film is Mother Vera. Would you like to talk about where that one is at the moment?

Cécile: Sure, yeah, so Mother Vera is a film that's been made over six years and it came out actually of a photograph as a co-director called Alice Tomlinson. And she was doing a project on Christian pilgrimage and I was assisting her on this fine art photography project.

And we did many, many trips to Lourdes for this project, in France. And I was translating, and helping with the camera because she was using a big old camera that's heavy and requires a lot of setting up. And we had one kind of chapter of the project in Poland and it was there that we met Mother Vera and Alice took this amazing photograph of Vera and that was the beginning of our relationship with this woman who is an orthodox nun from Belarus.

And she's quite young, she's in her 40s. I always say that because people imagine it's going to be someone in their 90s, if you say you're making a film about a nun. Yeah, so we've worked on it for six years, and the film is now out touring festivals, it premiered in Switzerland, and it's showing in London on [Sunday 13 October 2024 at 15:20, and Wednesday 16 October 2024 12:30] (Tickets here).

Bryan: Amazing.

Cécile: So, anyone who's interested should come.

Bryan: And that's part of the London Film Festival, right?

Cécile: Exactly.

Bryan: Yes, I will be there, that's amazing.

Cécile: Yeah, great.

Bryan: So, you were helping with the camera, this is a film camera in France, is that right?

Cécile: This is photography.

Bryan: Oh, photography.

Cécile: Yeah, with Alice. I was helping with her photography.

Bryan: And, how did you get into it in the first place? Like, how did you know how to use cameras?

Cécile: Yeah. Good question. How did I get into it? So I guess I'm pretty much a hundred percent self-taught. In terms of picking up cameras and light and all of that.

I've done little courses along the way, but really my degree was in Hispanic literature. But what I wanted to do, which was always my plan when I was younger, was study fine art. And that kind of didn't happen. I veered off into literature and languages. And through my degree and writing and reading, I realized, well, I can combine composition, aesthetics, beauty with research in documentary. So that's kind of the beginning of how I realized this is really exciting. This is what I want to explore.

Bryan: That's amazing. I studied literature as well. Which period of Hispanic literature and what area of the world were you interested in or was it?

Cécile: Yeah, it was a mixture. I did a lot of Golden Age stuff, which was insanely difficult to read in Spanish. Yeah. And that was a really good way into the deep end and to be really challenged by language, by this new language. And then when I came to the contemporary stuff, that meant that it was much easier to kind of crack through.

And there's a particular writer in contemporary Spanish literature who I love, Juan José Millás.

And in a way that was kind of, yeah. A little indicator of what might be coming in terms of making documentaries and kind of the way the gaze and the way that I would find to make films. He is a writer who manages to take everything that's kind of normal and make it seem extraordinary. And everything that's extraordinary and make it seem normal. It kind of turns things on his head in this on, and it's on their head in a quite magical way.

Bryan: Is it magical realism?

Cécile: No, it's not magical realism.

Bryan: Mm-Hmm.

Cécile: And then we had actually at university one course, which was creative writing, and I never imagined that I would enjoy creative writing and we had to write pieces that were only 500 words long.

Bryan: Oh wow. Microfiction?

Cécile: Yeah. Yeah. Which was this genre that was kind of emerging, I think, in the 1970s in Spain.

And they were being published in newspapers. So different writers would write 500 words, that was quite personal and it was kind of a mixture of literature and journalism. And very condensed, only 500 words.

Bryan: So… Potent.

Cécile: Yeah, quite, yeah, potent. And having a go at writing a few of those. I think it was the fact that it was able to be, it was personal.

Yeah. Yeah, and also storytelling. It was so new for me to write in that way. And yeah, that was very exciting. And I think the combination of Millás and his way of telling stories and then exploring myself, that way of writing and inventing, but also it coming from real, from your own real experience, which I guess all writing does, right?

Bryan: Yes, the good writing does.

Cécile: Yeah, exactly. So that was kind of like an unexpected experiment, which I think was a precursor to. Yeah. Okay, like I can, I can have this kind of very personal perspective and view on some of something that's real and shape it with my lens in writing. And then that was then transferred into making films later and I think built my confidence and kind of having a creative view in a new way that wasn't just drawing and painting.

Wow. Because I'd always been drawing and painting.

Bryan: So do you feel that the kind of crystalline nature of that short writing influenced you the way you saw the world or your cinematography?

Cécile: Did it influence that? No, I think it was more about reaching inside.

Bryan: Right.

Cécile: And being like, okay, these personal experiences one of them was about languages and speaking different languages and how that reflects different parts of who we are.

Like, I feel like I'm quite different as a person in Spanish and Italian than I am in English, for example. I think it was more about that. It was more about showing a part of myself in a different way.

Bryan: Right. Tell me more about what you're like in Spanish or Italian or French versus…

Cécile: English?

Bryan: You don't have to give an exhaustive description, but I'm curious.

Cécile: Well, it's quite funny I have a Spanish friend, for example, who she would just kind of like leap back when she hears me speak English, she said, you sound like a man, you know , and I guess I probably feel more expressive in myself in Spanish, and more relaxed.

Bryan: More formal in English?

Cécile: Yeah, I think so, but it's cultural, obviously, isn't it?

So yeah, probably more withheld [in English]. Maybe I'm funnier in Spanish But it feels different it feels like you're I'm channeling a different kind of version or something .

Bryan: We read Borges, a story last night for this discussion group that I do in London, one called “The Wait,” which is in Labyrinths. Have you read much Borges?

Cécile: No, I haven't actually. I remember when I was studying there was a friend who was reading him and yeah, he wasn't in my, in my pool at that time.

Okay. But yeah, I mean, he keeps coming in. This is another example of him coming in. Yeah, especially the labyrinthic. Yes. Which is something that came up quite strongly in Mother Vera, of somebody who's circling in this quite enclosed Orthodox reality. with a very heavy past and you know the enclosed nature of being an incumbent and the rituals and the repetition and the kind of a little bit going around in circles so yeah

Bryan: And how did you come to meet her you mentioned that you were with Alice when you did but was it completely random?

Cécile: Yes, it was. So we went to Poland because there was a big pilgrimage. This photography project that she was doing was about pilgrimage. There's a big pilgrimage happening there, and there were thousands of people and we spotted her with a donation box and she's very, very striking.

So you kind of notice her and Alice went to speak to her and explained we're doing this project and, you know, Vera being Vera, immediately was like, yes, of course, I would love to be photographed. So then, yeah, we set up the camera and took a picture and very quickly, within about 10 minutes, she said, you must come to Belarus.

Bryan: Right.

Cécile: I live there with 120 sisters, I work with horses, we later found out she's essentially a horse whisperer.

Bryan: Yes.

Cécile: And she was saying there's 200 men who are living there in rehab, I mean it just sounded unreal, I just thought wow this is, this is crazy. Crazy. And we ended up going, I think it was about a year later because Alice's photography project won a prize, which gave a little fund.

So we went initially to make a short film. And then when we discovered everything that she had spoken of it became, yeah, it felt like there's quite a lot going on here. There's a lot here. And for me personally, like the more I got to know Vera the more it became clear that there was just a very powerful personal connection.

I could really relate to her quest. A sense, a strong sense of an incredible breadth in one person who has this kind of striving for transcendence and being in touch with the divine or, you know that kind of spiritual side, but then also somebody who, she's very earthy and if you see her with the horses, it's very, very sensual, you know, and those opposites really resonate.

So yeah, I mean, that really, for me, is where a film comes from is a personal connection with somebody and something that ignites and then it just feels urgent.

It's like, right. Okay. There's definitely, it's like a relationship or falling in love or, there's something that emerges like a spark and you know, it's got mileage.

Bryan: You feel like you can't resist or something?

Cécile: Yeah. And you just know that it's unspoken between you, but you know, there's something that's gonna be explored. Something that needs to be unveiled together.

Bryan: So tell me more about how her quest resonated with you or, yeah, what was your, did you feel you were on a parallel quest?

Cécile: Yeah, in some ways. What was it that resonated? It was. I mean, I can't really say that much without giving away the story, but I could sense basically, there was a kind of spiritual alignment, which sounds quite crazy because, you know, [Belarusian] Orthodoxy is quite austere and definitely not anything that I knew about before. But before meeting Vera, I could sense that her kind of striving to connect with something spiritual, that probably is closer to nature or the cosmos, you know, without getting too kind of hippie-ish and kind of woo woo about it.

The way that she talked about her spiritual journey was often within orthodoxy, but then every now and again. There was a little hint, and I feel like she would say these things, that wasn't within the correct language of Orthodoxy and she wasn't really allowed to say it, but then it would kind of come out or I would understand it. Very subtle things.

So really it's that, and also the physicality. Right. You know, I was just like, I could really relate to those two. I'm drawn to extremities, as well.

Bryan: Yeah, me too. .

Cécile: Yeah. I'm really into that. It's fascinating. People who touch the limits of yeah. The limits that we have. All of the limits.

And we later discovered as we got to know her better, that she had been. struggling with heroin addiction in her life before she entered the monastery. And yeah, I've noticed it's a pattern in my life. I am drawn to people who are quite extreme.

Bryan: And do you think that it's extreme in sort of two directions?

Because you kind of mentioned austere orthodoxy, which I guess could represent a kind of turning away from life or renouncing life. But then you've also mentioned the embodied physicality and the embrace of nature, which is like life-affirming in a way. Do you think it's that polarity that attracts you?

Cécile: Well, there's something in the austerity, which I feel is not turning away from life. I feel it's like a sculpting and a digging to go deeper and deeper. And I find that very interesting, the control and the limitations that we can put around ourselves that are sometimes necessary in order to go into those depths.

And I suppose that's probably the polarity, is the discipline and the ritual and the rigidity of that, that it sometimes in life can be necessary to have, to be able to, you know, Get through what you need to get through. Or like, you know, I would think of it as, you know, being able to be, feel connected, essentially, and feel connected to the divine.

Ultimately, that's probably how I would phrase it. And then the other side with nature and that connection feels very expansive, but it's kind of the same thing, isn't it? And that’s what the film is about. It’s about her search for connection with herself through community and through the horses, through nature through the drugs, of course, before she went there.

Bryan: It’s very much a search for connection, isn't it?

Cécile: Yeah.

Bryan: Or to a higher power or something.

Cécile: Exactly. And we had this amazing editor who came on board to make a trailer. And when he watched the film, he came back, and luckily he really liked it. He said, “Yeah, I want to make this trailer.” And he said, “I just had a feeling watching this film that this person is quite alone, and she wants to be connected.” And I nearly fell off my chair. I think the thing is, for cinema, that often you don't really know what you're making until it's made.

I don't know if that's the same with writing, but it becomes very clear when there's a sharing with the world and somebody comes back and reflects back.

Bryan: Yes.

Cécile: And the way that you understand what's been made is different, it shifts.

Bryan: Going back to the point about good writing coming from experience or intuition, yeah, Schopenhauer has a point about this where he says that good art comes not from concepts, but he has a platonic version of the “Idea.”

So it's a kind of knowing that's beyond conceptual knowing. And he thinks that good art comes from there. And as a result of [the Idea] being this source, artists in the process of making art never know why they do what they're doing. It's not explainable at the level of concepts. And so he almost suggests that the better the art is, the less it's possible to know whether you're doing the right thing.

Whereas if you're doing some kind of derivative rearrangement, it's already in this conceptual realm that allows for rearrangement. It’s easier to talk about something like that.

And you and I have talked about how difficult it can be to talk about works [in progress], haven't we?

Cécile: Yeah, it's so hard. Yeah, it can be. I can totally relate to that, to what he's talking about there. I mean one of the biggest lessons and things I learned with this film and every film I've made, but particularly this one because it's my first feature is that there's such a process of getting lost. And that's quite painful and difficult, and I found myself really resisting that. And for the next one I now know that that is a part of it and it, you can't avoid it, it's important and in terms of being beyond concepts.

I think the main driver, for me personally, with filmmaking, is intuition, and just surrendering to that intuition and knowing that there is a thread through all of this journey that's leading to something that will be coherent at the end, but that full coherency of what you're making is not coherent. Like it needs to be made and it's being kind of knitted, you know, and that's what I love about documentary. It's knitted within you, in engagement with reality in somebody's life as it emerges.

And it's so amazing to be able to engage with that and kind of play with it and receive it as it unfolds.

And there's just a deep trust that needs to, because also, documentary, independent documentary is so risky. Nobody will come on board until really late, so you have to develop loads of it. I don't want to start opening my complaining box, but. It it's a huge risk. It's a huge battle, right? Because, yeah, it's so hard to be supported and also, you don’t know where it's going to go.

Bryan: Right.

Cécile: And you don't know, you have to trust yourself that you're going to get it all in the bag because you could get to the end and realize you, well, it could be the end for some reason and realize you haven't quite got there. So you need a lot of faith, and trust.

Bryan: Because there's a kind of opposite requirement. Making something versus selling it are quite different things, right? And in order to sell it, you need to be able to describe it. But description is like not what's called for when you're making the art or something like that.

Cécile: No, it's all backwards.

Bryan: Yeah. It's backwards.

Cécile: So you have to make it up.

Bryan: Yeah. So then you're making a kind of secondary fiction about what it might be be like. Did you have that experience?

Cécile: Yeah. Yeah. The pain. I cannot tell you the pain of trying to write it in the beginning, and you're making, as you say, like a secondary fiction and then just amending it amending it and amending it as you go, and as it's being born.

The writing is really important. I really resist it and it's hard, it's 90% hard and 10% extremely joyful when it starts crystallizing and connections are made and all of that stuff, intuition you're trusting starts to be visible.

Bryan: When you say the writing, what kind of writing are you referring to?

Cécile: So yeah, kind of continual writing of like a treatment or a synopsis, trying to sculpt and understand what you've filmed and where you're going. Trying to get out of being lost.

Bryan: Yeah, being lost. Do you feel like you're in sort of uncharted territory when you're making it?

Cécile: Yeah, but that's what's so exciting, right? And that's where you know it's worth doing it. Yes. And in a way it's not because it's so personal.

Bryan: Because it's a documentary, you mean? Or because you already have an internal sense of it?

Cécile: Because the connection with the protagonist is so personal, it's like it's familiar in a way, but then of course it's also a discovery.

Bryan: There's a way in which it makes you feel kind of insane because it's like in order to make something original you have to go somewhere that no one else has been. So then you're like striving towards this place where everyone treats you like you're kind of crazy, because they don't know where you're going, and then you actually can't describe why you're going in that direction.

And then it's very isolating, isn't it? Because even with a close friend, like all they can offer emotional support, but they still can't understand what you're doing or why. Right?

Cécile: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. It can be. Yeah, hard to tow that path and just keep going and feel isolating, definitely.

I mean, it's funny because I think your journey is similar to my journey and, you know, making films. But my kind of chip on my shoulder or my Insecurity about it is I didn't study cinema. I studied literature. And so I've always thought oh god, how can I justify what I'm doing?

But in a way it feels like a complete opposite of you. You're having conversations with all these dead philosophers and you know, your knowledge of the whole field is gigantic. But I think in a way with documentary and for me, particularly in my case, that not knowing really helps because it's the only choice really is to connect with that intuition.

And obviously there are inputs and there are influences and particular filmmakers that have really helped me, ignited something at particular moments. And those are kind of guides, but I think it's, I've noticed that it's also important to carry those on a deeper level and, and make sure that whatever you're focusing on is coming really from you.

And it's almost like unlearning anything.

Bryan: Right. Yes.

Cécile: And I'm pretty lucky cause I didn't learn in the first place. Yeah. I didn't have a good, yeah, strict Yeah, education in cinema, it's all been kind of hodgepodge bits here and there.

Bryan: Beginner's mind.

Cécile: Yeah, and that's the thing, it's keeping it fresh.

And how does that work with the second film?

Bryan: Right, yes. How do you access that or do something new when it's actually the second time, right?

Cécile: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Bryan: I'm actually in a semi-equivalent state, I guess, because I also studied literature. I've never studied philosophy formally. So I'm coming to it as an outsider in some ways.

And I like you, I have anxiety about speaking to people who are formally trained and have a PhD in philosophy or you know what I mean? Who have been more seriously educated in this way. Whereas I do feel like an outsider within [philosophy], which is both a burden and an advantage somehow. Do you know what I mean?

Cécile: Yeah.

Bryan: Because I don't know the rules and therefore I can just do whatever I want, basically.

Cécile: That's really handy.

Bryan: Yeah.

Cécile: I mean, you kind of know them a bit, probably, but like, yeah, to have not officially been taught them, I think, gives you a free pass.

Bryan: Yes, exactly.

Cécile: And that's a great, or better, starting point.

Bryan: And for me it means crossing boundaries. Do you know what I mean? Like I don't have to stick to a period or anything like that because, you know, I'm not studying the Early Modern Period. You know, once you get into academia, it's very narrow, whereas my interests are very broad.

So, yeah. Would you like to talk about your influences? I would love to hear more.

Cécile: Yeah, sure. So there's one, there's the first most important one really in terms of being fundamental in a kind of internal decision of like, oh, wow, this is what I want to do. And that I discovered him when I was living in Rome after university working in this production company trying to speak Italian, when I was really speaking Spanish, it was all a bit of a crazy situation trying to answer the phone in Italian. It's really scary.

Anyway, I discovered Gianfranco Rossi, who is an incredible Italian film director, and he spends a long time living with communities and protagonists before he starts filming.

And yeah. He made this film, which was about, so it's very similar to Nomadland.

Bryan: Oh, yes.

Cécile: And it was kind of like he made the original one.

Bryan: Right. Okay.

Cécile: And it's about a bunch of people living in a desert in California who are kind of outcasts and who are not really… They've chosen to live very different lives and kind of, in some cases, kind of fallen off the sides and they've come together in this, in this community and he spent a long time getting to know them and the kind of point of view, the kind of love that he had for these people, and the way he manages to film in a way that elevates what's happening in front of the camera and reality to something beautiful and poetic that brings like a whole layer of all these other things, all these other kind of readings of what's going on. I don't know if that's a very good way to describe it, but when I saw his work, I just thought, wow, this is like fiercely creative.

Bryan: That's amazing.

Cécile: Yeah. And this is what's possible, a documentary, that's what I want to do.

Bryan: And what is that film called?

Cécile: It's Below Sea Level.

Bryan: Below Sea Level, okay.

Cécile: Yeah, because they're not far from Los Angeles and below sea level and in their own pod, their own independent kind of community that feels quite anarchist and incredible people.

Yeah. It's a brilliant film.

Bryan: I saw Nomadland recently on a plane and also saw The Taste of Things alongside it. I watched them back to back and they are both films about grieving. It's a weird combination. Have you seen The Taste of Things?

Cécile: No, you were telling me that you thought I recommended it to you. I really want to see it. I haven't got around to it.

Bryan: But you saw Godland recently. Yeah. What did you think?

Cécile: I thought it was fantastic.

Bryan: Yeah, it's amazing, isn't it?

Cécile: Yeah, I just thought he was So tortured and brilliant, like it's such an interesting character.

Bryan: And like your film, it begins with photography. Yeah.

Cécile: Yeah, exactly. Yeah.

I was thinking a lot about the parallels with Mother Vera. Yeah. It's a very tense film. I like that. How it just kept getting more. You're cranking it more. I love that. It's like a volcano. Of course, there is literally a volcano in it as well. What did you think of it?

Bryan: I just think the way it's shot is incredible.

The setup of it, I won't spoil it too much for people who haven't seen it, but it is so intriguing, right? This set of photographs and this kind of attempt to fill in the gaps. There's something about that setup that I just find irresistible. It's like a kind of, you know, detective work. And it just brings attention to how much is lost, you know, we have these vast spaces vast expanses of time, and just how difficult life was for so much of history. There's something about crossing that Greenland terrain that just is just a reminder of how everything used to be. “This is how we were,” or something.

Cécile: Yeah. The physicality of it. The trials. Yes. The traveling across all that landscape and the hideousness of him becoming ill and, oh God, it's desperate, isn't it? In moments. Yeah. Yeah, yeah. And how far away we are from that now?

Bryan: Are there other influences that come to mind?

Cécile: Are there other influences? There's a really beautiful film which is essentially like a painting, which probably you've seen called Silent Light.

Bryan: No, I haven't.

Reygadas, this Mexican director And he talks, that director talks a lot about presence.

And it's a love story, essentially, of betrayal. And it's it's very slow and very beautiful. The nature in it is extraordinary. And the beginning of it you can't really say what it is but it's extraordinary nobody had ever done that before, as far as I know. He's just so bold that director to take so much time with each individual shot and really be with that actor who are all, I think, non actors, and with the emotion, and forcing you to be with it to be to put you essentially there with them and slow down almost so you can feel their breathing, heartbeat. And what he calls presence, like he's always trying to capture presence or create presence, I think is what cinema is all about.

And Béla Tarr did, I mean, we saw, the other day, Sátántangó.

Bryan: Yes, we saw all seven and a half hours of Satan's Tango in one go. Well, but there's intervals, right? Two intervals. But that is an exercise in. Patience, glacial filmmaking and presence in a way, right? It just, it does put you, it forces you to be with them for far longer than you want to or than is normal in filmmaking, right?

Cécile: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. It really pushes way over the limits of what's like, not especially with what's being made today. But that journey that you go on, if you go with it, you know, is incredible.

Bryan: I know I've asked you about him before, but which of Refn's films have you seen?

Cécile: I haven't seen any of them. I had him on my list of stuff.

Bryan: Yeah. This is the director of Drive, Only God Forgives and The Neon Demon. Those are his feature films. And then he made a series for. Amazon called Too Old to Die Young, and that one is 10 hours. It is like, that is very Béla Tarr in its patience, let's say, and extraordinarily beautiful, and really lingers too long in many ways, but it, that makes it, I feel like when I talk about these films, it's hard not to make them sound like painful and boring, but they, it's not, it's It's, it's irresistible.

It's like, I don't know, that, that series is, is incredible. And then he's made another one for Netflix called Copenhagen Cowboy recently. They're both difficult watches. I would not recommend them to everyone, but I would recommend them to you, actually.

Cécile: I mean, yeah, sometimes it is painful. I told you I went to see The Turin Horse.

Bryan: How was that?

Cécile: It's a challenge and I could feel it palpably in the cinema towards the end. There's something around the kind of misery and suffering of these protagonists and the repetition the monotony of it.

Bryan: Right.

Cécile: And when it repeats again towards the end you can feel like, “Oh, I'm not sure.” I mean, I did have a moment thinking, “I'm not sure if I can. I might go mad.” You know, I had a similar moment with The Act of Killing.

Bryan: Oh, yes.

You know, at the end that kind of horrific, I had a similar kind of switch in my brain. I thought, “Oh my.” It's scary, but I think that's so powerful that cinema can provoke such violent feelings.

And that's what it's all about, right? Is togo, maybe not only that extreme, but to feel it in your body, I think, is a real achievement. Cinema needs to be sensual and physical, like is it going to be? Is this gonna be?

Bryan: Yeah. I think Kafka said “We should only read fiction that stabs and wounds us.” And I've always been sort of partial to that view of art.

Cécile: Yeah.

Bryan: Like, this is actually probably why I wanted to watch Satan's Tango with you or with other people in a cinema. Beause when I first watched it [alone], I was like, this is so good. This is good. Right? This is kind of funny. And like, there's a kind of insane humor on the other side of all the darkness and the unrelenting bleakness or something like that, you know?

Cécile: Absolutely. I think Béla Tarr really does have a sense of humor and he's kind of playing with us, you know, and there's moments, I can't, there's a moment in the film where there's a guy kind on his knees and in kind of awe at this view of that ruin with. All this kind of mist floating around it and there's some, I don't know if there's a voice though, but it feels very mystical and kind of transcendental.

And then the other guy, I can't remember what he says, he's like, what is like, “You've never seen…”

Bryan: “You've never seen fog before?”

Cécile: Yeah, exactly. And so it's quite good how he just, yeah, Béla Tarr just kind of slaps it down. Yeah, exactly. Let's not get too ahead of ourselves.

Bryan: Yeah. Yeah. Cause that scene, There's a lot of parts of Satan's Tango that are a bit Tarkovsky, but then he undercuts it, right?

He never lets you go into that kind of Kurosawa, Tarkovsky, slightly mystical space, that full release.

Cécile: Yeah, exactly. Floating off into the cosmos. He's like, no, let's bring you back down. Let's bring you back down.

Bryan: Because actually…

Cécile: The reality is hard, drudgery. Yeah. Yeah. Apart from maybe the scene with the child.

Bryan: Yes.

Cécile: Yes. Yeah. Where that... I mean, you couldn't do that then, could you? No, that tragic scene. Yeah, that does reach into something.

Bryan: We should wind it down here then, I think. Yeah. It was really great to talk to you and I hope to have you on again.

Cécile: Yeah, I would love to come on again. Thank you so much for inviting me. It was great chatting.

Bryan: Thanks so much, Cecile.