When I was a little less than two years old, I very nearly died.

At first my parents thought I had the flu. But over about a week and a half, and three doctors visits, I became sicker and sicker, eating voraciously and vomiting — and losing weight rapidly.

Through a fortunate series of events, and my mother’s search for my symptoms in the Merck Manual, I was diagnosed ten days later with Type 1 Diabetes. By that time, I had lost 20% of my bodyweight, and was dying of dehydration.

The day of my diagnosis was the day my brother Kevin was born, in a different hospital.

After ten days in hospital, I was released — with a prescription for four or more fingerprick blood tests and three or more injections of insulin, every day, for the rest of my life.

Type 1 diabetes is incurable and fatal if untreated with insulin. In the 38 years since being released, I am still alive thanks to constant vigilance. First my parents’ vigilance, and, then, from a young age, my own. From the age of 7, I gave myself my own injections. And from the age of 13, I was fully in charge of my own care, which is a matter of life and death.

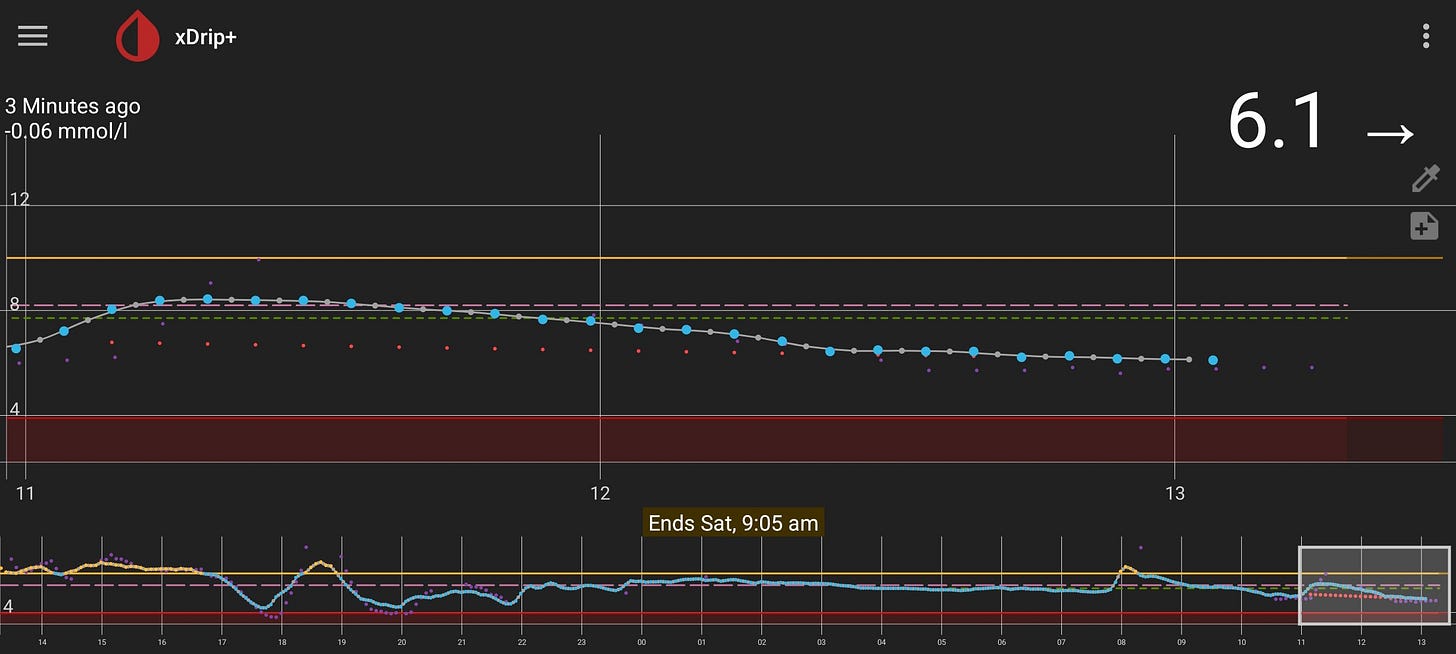

The technology has improved, but it does not eliminate the need for continuous vigilance over what, how much, and when I eat. I must constantly monitor my blood sugar levels, and make decisions about insulin delivery.

I no longer do fingerpricks, but instead have a Dexcom G7 (a “continuous glucose monitor”) inserted into the skin beneath my abdomen. I no longer do 3-4 injections, but instead have a t:slim insulin pump which delivers insulin via a tube connected to a cannula under the skin of my abdomen.

If this sounds painful, it is. The CGM and pump is more convenient than multiple fingerpricks and injections, but still deeply inconvenient, usually uncomfortable, and sometimes painful.

My friend Pen interviewed me recently, on a walk in the woods near my house, because I’ve been writing about this experience for an academic paper I’m working on, which is an introduction to Neither/Nor.

I’ve also been struggling more than usual with the hypervigilance which this condition rewards. There’s even a term for this exhaustion: “diabetes distress” and “diabetes burnout.” But since getting the continuous glucose monitor in September, it’s actually gotten a bit easier.

You can listen to the podcast here, or search for “Bryan Kam” or “Clerestory” on any Podcast app. You can also click here to listen on other platforms.

All the best,

Bryan