Durkheim and classification

On the opening of Primitive Classification (1903)

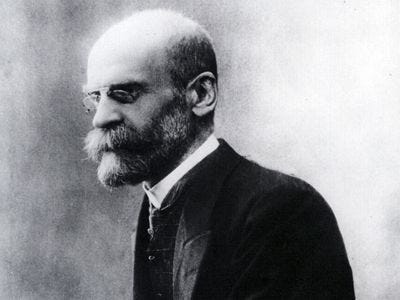

In working on Neither/Nor, I’ve recently become obsessed with Émile Durkheim (1858–1917), a French sociologist writing at the start of the 20th century. This is because one of his interests is very squarely one I share.

That question is:

How do we as humans come to group things into concepts?

One response to this question is called “naïve realism.” In this view, it’s just obvious that there are objects in the world, and we perceive them as they are.

If we also find it obvious that we classify these objects under concepts because the objects come to us classified into groups, then this can lead to the correspondence theory of truth.

I covered the correspondence theory obliquely through a series of quotes which call it into question, in A Brief History of Truth and also in a few Tiktok videos.

The correspondence theory basically says that “truth is making a statement that corresponds to the reality.” But this assumes that reality is somehow independent of perception and speech, and also that statements are somehow verifiable against that independent “reality.”1 Critically for the purposes of this article, because propositions use concepts, it assumes that conceptual groupings are basic and straightforward. These are big assumptions that would themselves need support.

At this point, for realists, some courage and patience will be required, because there’s often a knee-jerk response that comes when such fundamental assumptions are called into question. One of the most common responses I’ve experienced is the immediate desire to dichotomize: “If there is no independent reality, or if it is impossible to verify it, then everything is meaningless!” This is not necessarily true. And some obvious alternatives to the correspondence theory, for example nihilism or relativism, are not necessarily the only alternatives.

I also find it interesting how the distress from such questions seems to lead to a desire for foundationalism, some kind of firm ground to stand on.

But rather than starting to dig, once again, courage and patience with discomfort are required.

So what did Durkheim write?

Durkheim’s now-regrettably titled Primitive Classification, from 1903, looks at how conceptual groupings themselves arose. I’ll take a close look at his opening in detail which he titles “The Problem,” in some detail, because it’s so important to my project. I find this stuff mind-blowing.

The Discoveries of contemporary psychology have thrown into prominence the frequent illusion that we regard certain mental operations as simple and elementary when they are really very complex. We now know what a multiplicity of elements make up the mechanism by virtue of which we construct, project, and localize in space our representations of the tangible world.

So Durkheim asserts that psychology has shown that apparently simple mental operations are, in fact, very complex.2

This goes hand-in-hand with my historicist approach in Neither/Nor. I’ve found that most parts of the past which I might naïvely have regarded as simple have incredible complexity whenever I’ve drilled down. (I’ve also never met an historian who has started a sentence with like “Well, it’s all very simple!”)

What I mean by historicist is that I treat things, including the usage of concepts themselves, as having a history.

I also want to draw your attention to the fact that it is space that is called into question. This is important because space and time are, in Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason (1781; A22/B37), the two “forms of the intuition.” These forms, for Kant, are a precondition for any experience at all.

Durkheim continues:

But this operation of dissociation has been only very rarely applied as yet to operations which are properly speaking logical. The faculties of definition, deduction, and induction are generally considered as immediately given in the constitution of the individual understanding.

In other words, many of the steps which are absolutely required for logical thinking have been assumed to be “innate.” This includes “definition,” “deduction,” and “induction.”

Why does innateness bother me?

One of the driving forces in Neither/Nor is my lifelong dissatisfaction with the Law of the Excluded Middle, which states that for any proposition, either that proposition is true or its negation is true.

I’m fine with this in many contexts:

Either I locked the front door or I didn’t lock the front door.

Either I’ve met this person or I haven’t met this person.

But in other contexts it starts to become uncomfortable:

Either God exists or God does not exist.

Either I am Asian or I am not Asian.

Tertium non datur is the Latin way of stating this rule, and it translates to “There is no third option.” But I often want a third option! I’m mixed race, for example.

I’ll pick up next week with more of Durkheim. But for now it’s important to know that this law is indispensable for classical logic, and certain mathematical proofs (by contradiction, for example) depend on it.

Best,

Bryan

As wikipedia notes, it could instead assume an idealism whereby the truth corresponds to the mind of a supreme Being.

I actually don’t know who, for Durkheim, has called into question the simplicity of our “representations of the tangible world,” but I suspect Hermann von Helmholtz (1821–1894), whose work on perception continues to be fruitful today. Some other guesses are the physiologist-philosopher William Wundt (1832–1920) and the psychologist-philosopher William James (1842–1910).

This is helpful. Look forward to more. All of this is relevant to the absurdity i experience in political discussions where people conform to ideologies and refuse evidence that points to a '3rd' way.

Do you see aporia as a release valve from the limitations of classification?

Perhaps the law of the excluded middle applies only for well-defined things.

What does it mean for "god" to "exist"? Lots of definitional arguments there.

What does it mean to be "Asian"? Sorites paradox land there.