Insatiable

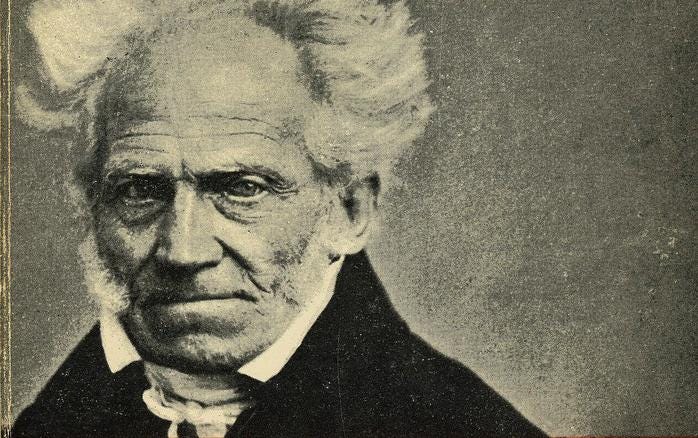

Schopenhauer's will

Today I’m writing to you about Arthur Schopenhauer’s will, which he argues is the “thing-in-itself,” i.e., that which exists independently of our mind. This is equivalent to Kant’s noumenon; you might think of it as the nature of nature. I wrote about his relationship to Kant last week.

For Schopenhauer, the characteristic quality of nature is the will, which is insatiable, never satisfied, and endlessly striving. This is true for the will as manifested in the force of gravity (a rock striving to be lower), a plant (striving toward sunlight), an animal (striving for food or other needs) — and of course it also describes human striving.

Here’s how Schopenhauer describes the will in nature (emphasis mine):

[The will] always strives, because striving is its sole nature, to which no attained goal can put an end. Such striving is therefore incapable of final satisfaction; it can be checked only by hindrance, but in itself it goes on for ever. (WWR I, §56)

The forces of nature can be impeded or obstructed, but never satisfied.

For if, according to its will, all existing matter were united into a lump, then within this lump gravity, ever striving towards the centre, would still always struggle with impenetrability as rigidity or elasticity. Therefore the striving of matter can always be impeded only, never fulfilled or satisfied. (WWR I, §29)

Here’s how he describes the will made manifest in humans:

Now the nature of man consists in the fact that his will strives, is satisfied, strives anew, and so on and on; in fact his happiness and well-being consist only in the transition from desire to satisfaction, and from this to a fresh desire, such transition going forward rapidly. For the non-appearance of satisfaction is suffering; the empty longing for a new desire is languor, boredom. (WWR I §52)

For the human subject, unlike nature, there are very brief moments of satisfaction before the will kicks in again, producing a new desire with a new object.

Schopenhauer thinks that there are two ways to escape the endless loop of desire and suffering. For him, both are temporary measures, though a third more permanent one, “resignation,” is available to certain saints.

Perception

The first way is through the cultivation of will-less and ego-less perception. Schopenhauer calls this the “purely objective contemplation” of any object. By “objective” he just means “lacking a subject” or a sense of self. Note that it also includes mental images:

We can withdraw from all suffering just as well through present as through distant objects, whenever we raise ourselves to a purely objective contemplation of them, and are thus able to produce the illusion that only those objects are present, not we ourselves. Then, as pure subject of knowing, delivered from the miserable self, we become entirely one with those objects, and foreign as our want is to them, it is at such moments just as foreign to us. Then the world as representation alone remains; the world as will has disappeared. (§38)

Art

The second way, which I mentioned last week, is through art. Schopenhauer thinks that being intelligent mostly makes a person’s suffering worse, but that one compensation for this suffering is that the intelligent can ameliorate their greater suffering through a finer appreciation of art:

The pleasure of everything beautiful, the consolation afforded by art, the enthusiasm of the artist which enables him to forget the cares of life, this one advantage of the genius over other men alone compensating him for the suffering that is heightened in proportion to the clearness of consciousness, and for the desert loneliness among a different race of men, all this is due to the fact that, as we shall see later on, the in-itself of life, the will, existence itself, is a constant suffering, and is partly woeful, partly fearful. (WWR I §52)

Art, Arthur thinks, temporarily suspends the cycle of desire and suffering. In this passage, it seems to apply both to the artist making art as well as the art’s audience.

This view of art, and especially Schopenhauer’s view of tragedy, clearly inspired Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy (1872), as I mentioned last week.

Artists, for Arthur, take on the suffering caused by the will to produce art. Those who experience the resulting art objects are temporarily released from the affliction of the will.

He continues:

The same thing, on the other hand, as representation alone, purely contemplated, or repeated through art, free from pain, presents us with a significant spectacle. This purely knowable side of the world and its repetition in any art is the element of the artist. He is captivated by a consideration of the spectacle of the will’s objectification. He sticks to this, and does not get tired of contemplating it, and of repeating it in his descriptions. Meanwhile, he himself bears the cost of producing that play; in other words, he himself is the will objectifying itself and remaining in constant suffering. (§52)

The very artifice of art makes it knowable in a way that is harder to achieve with direct perception. While we are absorbed in this kind of knowing, thinks Schopenhauer, our ego abates, and our will ceases to strive on our behalf.

Unfortunately, in most cases this does not last:

That pure, true, and profound knowledge of the inner nature of the world now becomes for him an end in itself; at it he stops. Therefore it does not become for him a quieter of the will, as we shall see in the following book in the case of the saint who has attained resignation; it does not deliver him from life for ever, but only for a few moments. For him it is not the way out of life, but only an occasional consolation in it, until his power, enhanced by this contemplation, finally becomes tired of the spectacle, and seizes the serious side of things. The St. Cecilia of Raphael can be regarded as a symbol of this transition. (§52)

In my view, this is probably related to the artistic “relief valve.” I suspect that the meditative states, which can make art out of any perception, result in the same suspension of the will. It’s just that it’s easier to become absorbed in art than it is to become absorbed by other perceptions. I would guess that art is the easiest, then a walk in nature, then random perceptions — imagining a candle flame, seeing a dirty street, the inside of your eyelids, and so on.

Rapacious

Insatiability is the nature of the will for Schopenhauer. Since the will characterizes both nature and human nature, we are trapped in this cycle of suffering. If his sounds similar to Buddhist Saṃsāra, this is no coincidence, as Schopenhauer was familiar with Buddhism.

For Schopenhauer, nature strives constantly. Since humans share this will with nature, human nature itself dooms us to perpetual striving without satisfaction.

In a sense, insatiability provides a view of nature as scarce, at least in satisfaction. Therefore Schopenhauer does not recommend aligning with nature, which would mean wilfully striving for desired objects, since this is a fool’s errand. Instead, we should use the will against itself, to undermine desire. This, too, is not entirely unrelated to Early Buddhism, which uses suffering to study the three characteristics and thereby to undermine a sense of self and craving. But I would argue that this is only the first step in Buddhism.

Notice that this advice opposes us to nature; nature has will, and so do we, but we use our will to resist or subvert the will (and therefore, in some sense, to resist or subvert nature).

The idea that we are separate from nature a long Judeo-Christian history. Schopenhauer’s pessimism about nature may also spiritually align him with Hobbes’ view of the state of nature, Hobbes’ famous “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” in the Leviathan (1651). This is important, because Hobbes’ view of human nature views civilization as a solution to (rather than a cause of) the suffering we experience. You might say that Schopenhauer, too, views the type of consciousness afforded to humans by civilization as a solution to suffering. Rousseau (1755), who will spur Nietzsche on to his more mature inquiries, views civilization as a cause of the suffering we experience.

Next week I’ll contrast this opposition between humans and nature with the Taoist view of nature. Perhaps surprisingly, though Schopenhauer’s metaphysics contrasts starkly with the cosmology of the Tao, the practical recommendations of Schopenhauer and the Lao Tzu may not be so different.

Is Schopenhauer’s claim ontological?

Yes. He thinks Kant’s noumenon is the insatiable will. He views the will as being the way things really are, independently of humans.

But notice once again that the boundaries of both the inquiry and the solution have shifted since Kant.

Here’s how I see this as developing:

Kant was responding primarily to Locke (1689) and Hume (1748). For Kant, the central question is ontological (“How can we know what exists outside of our minds?”) — but his solution is epistemological (“We can only know the representations.”).

Schopenhauer was responding primarily to Kant. For Schopenhauer (1818), the central question is epistemological (“Is there another way to know what exists outside our minds outside of the representations?”) — but his solution is aesthetic (“Yes, through the body and will-less perception; but knowing this only shows that suffering is endless. So we should suspend the will through art and through direct perception.”).

Nietzsche was responding primarily to Schopenhauer (1818) in his early works, and to Rousseau (1755) in his middle works. For Nietzsche (1872), the central question is aesthetic (“How can the experience of art or philosophy relieve the suffering of life?”) — but his solution is moral (“They shouldn’t; instead we must turn suffering to our advantage, and life must be affirmed by living it rather than denied through abstraction.”)1

So the conversation has shifted from ontological, to epistemological, to aesthetic, to moral.

I think this is a typical pattern for philosophy to follow, and that the pattern occurs at least twice in antiquity, and again in the Renaissance.

Here are the questions in simple form:

Ontological: “What exists?”

Epistemological: “How do we know?”

Aesthetic: “What can we make or experience?”

Moral: “What should we do?”

None of these questions can be finally answered, and attempting to answer one often raises another.

As always, I’d love to hear from you! Please comment on this post if you’ve read this far so I know you’re out there :)

Thanks,

Bryan

This post is the fourth in a series. Here are previous entries:

I know it seems odd to call Nietzsche “moral” since he so strongly critiques traditional “morality”; but ultimately his question is more about how to live than it is about what exists. I could also call his position “pragmatist,” but I think that word is encumbered by a position on the nature of “truth,” which I think Nietzsche to some degree shares with the American pragmatists, but which is not at stake here.

I’ve been enjoying this series Bryan, keep it up! The idea of will being at the heart of nature is a strange idea that I will be thinking about…