Reasoning requires training

Logic can't both be basic and an achievement

I’m Bryan Kam. I endeavour daily to make philosophy accessible and relevant. To that end I write this newsletter and host a podcast called Clerestory. I’m also writing a book called Neither/Nor and I’m a founding member of Liminal Learning. In London, I host a book club, a writing group, and other events. My work looks at how abstract concepts relate to embodied life, and how to use this understanding to transform experience.

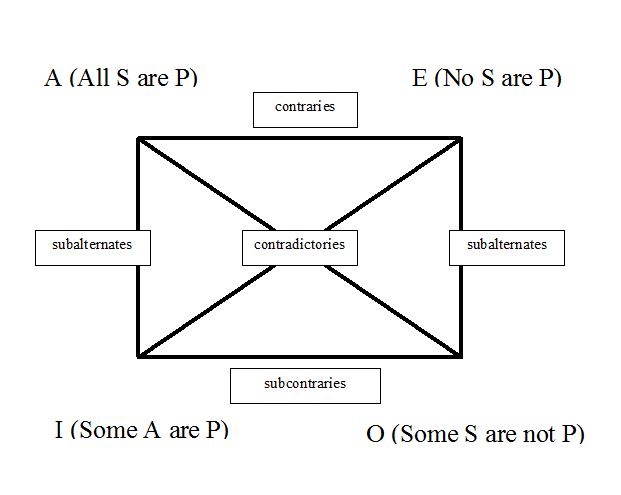

I’ve argued before, in “The Birth of Logic,” that logic is not a timeless and unchanging discovery, perfected by Aristotle and with no further developments until the time of Kant. A friend of mine, a logician, has said that Frege’s approach, which builds on Aristotle’s, still substantially modifies it

This is an odd feature I keep noticing about conceptual approaches. They often claim that something, in this case logic, is both basic to the universe and a basic aspect of cognition, and, at the same time, a massive discovery by Aristotle. For example, Kant’s forms of the intuition — time and space — are supposed to be preconditions to our having any experience at all. And yet his notions of time and space seem suspiciously Newtonian, as opposed to, say, Aristotelian. So how can Newtonian time, which ticks forward simultaneously throughout the universe, both be a massive and revolutionary discovery of a basic truth of the universe by Newton — and also basic to Kantian cognition? Obviousnesses in mathematics often seem to get similar treatment. If 2+2=4 is such a basic obvious truth that we use it as such in conversation, why do we need to teach arithmetic?

The standard view treats logic as simultaneously obvious but also a discovery. This creates a paradox: If logical reasoning is so basic to human cognition, why does it require training to master?

As a reminder, Kant declared that logic "since the time of Aristotle... has not had to go a single step backwards" and "seems to all appearance to be finished and complete" (B viii). See a fuller quote here. Today I’ll argue, against Kant, that it is not basic. I’m arguing that even syllogisms are contextual — we don’t naturally use them to reason outside of our experience.

Even Charles Sanders Peirce, who might seem to support the universality view, actually anticipated this problem. Rather than claiming logical reasoning comes naturally, he explicitly states that “we come to the full possession of our power of drawing inferences, the last of all our faculties; for it is not so much a natural gift as a long and difficult art.” So he recognizes that parts of it are basic, but others require training.

Here’s “The Fixation of Belief,” section II (1877). by Charles Sanders Peirce:

The object of reasoning is to find out, from the consideration of what we already know, something else which we do not know. Consequently, reasoning is good if it be such as to give a true conclusion from true premisses, and not otherwise. Thus, the question of validity is purely one of fact and not of thinking. A being the facts stated in the premisses and B being that concluded, the question is, whether these facts are really so related that if A were B would generally be. If so, the inference is valid; if not, not. It is not in the least the question whether, when the premisses are accepted by the mind, we feel an impulse to accept the conclusion also. It is true that we do generally reason correctly by nature. But that is an accident; the true conclusion would remain true if we had no impulse to accept it; and the false one would remain false, though we could not resist the tendency to believe in it.

To most of my readers, who will have been schooled in the West or by Western-influenced schools, this position may seem basic. Peirce is just saying that “reasoning” (which I would say is “using logic”) is about taking what we know and applying it to things we don’t know. He also says that we “generally reason correctly by nature.” He also seems to presuppose that the conclusions of logic are always correct, which may be true in most cases, but not in certain cases, like the later discovered Russell’s paradox.

I want to bring in Aleksandr Luria’s Cognitive Development (1936, but translated into English in 1976). In it, Luria records transcripts with villagers of differing levels of education in Uzbekistan, where villagers were coming under the Soviet education system. He found substantial differences in how readily people would use abstraction based on even just a year or two of education. Before formal education, they were perfectly capable of reasoning, but they tended to rely much more extensively on their own experience. Those with the least formal education tend to refuse to complete abstract syllogisms or counterfactuals, even though elsewhere in the conversation they show the ability to make the very same calculation when it is a matter within their experience. The transcripts really speak for themselves. Here’s one (p110), with the interviewer’s questions in bold:

Subject: Khamrak., age thirty-six, peasant from remote village, slightly literate.

From Shakhimardan to Vuadil it is three hours on foot, while to Fergana it is six hours. How much time does it take to go on foot from Vuadil to Fergana?

“No, it’s six hours from Vuadil to Fergana. You’re wrong . . . it’s far and you wouldn’t get there in three hours.”

Computation is readily performed, but condition of problem is not accepted.

That makes too difference; a teacher gave this problem as an exercise. If you were a student, how would you solve it?

“But how do you travel—on foot or on horseback?”

Slips back to level of concrete experience.

It’s all the same—well, let’s say on foot.

“No, then you won’t get there! It’s a long way . .. if you were to leave now, you’d get to Vuadil very, very late in the evening.”

Condition that contradicts experience is not accepted.

All right, but try and solve the problem. Even if it’s wrong, try to figure it out.

“No! How can I solve a problem if it isn’t so?!”

Refusal to solve conditional problem.

The transcripts show how readily problems whose conditions correspond to reality are solved, and how difficult it is for the subjects to accept conditions that do not hold true in their own experience and to perform the associated formal logical operations. Several examples show how sharply the ability to solve problems conforming to practical experience contrasts with the inability to solve problems whose conditions contradict this experience. These data convincingly demonstrate the degree of difficulty in trying to induce our subjects to perform formal logical reasoning independent of content.

In other words, though Kant assumes that logic is basic, Luria finds that it actually requires formal education. This supports the view that logic is a major achievement by Aristotle, and not something basic. Whether that achievement is a discovery or an invention, however, will have to be left for another post.

Moreover, reading Luria’s compassionate transcripts, we come to see that the Uzbek villagers are not reasoning in an inferior way. Instead, their reasoning is perfectly functional for the lives they actually live. When the interviewer gives them an incorrect statement as a premise, they rightly reject this. They also demand more experiential evidence. They famously refused to reason, for example, about polar bears in places they haven’t been (p107):

They refused even more decisively to draw inferences from the second type of syllogism. As a rule, many refused to accept the major premise, declaring that they “had never been in the North and had never seen bears; to answer the question you would have to ask people who had been tjiere and seen them.”

Rather than showing a cognitive deficiency, this shows specificity and a refusal to enter the unknown territory of abstraction. The refusal to extend claims outside of experience may not allow for “All men are mortal” type syllogistic logic, but it could protect its users from misinformation, for example. Though it may be tempting for those schooled as we were to regard this refusal as a cognitive limitation, it could also be seen as something approaching cognitive wisdom.

Meanwhile, here’s a passage from “Cognitive Consequences of Formal and Informal Education” by psychologists Sylvia Scribner and Michael Cole (1973):

The evidence that different educational experiences give rise to different functional learning systems comes primarily from the work of contemporary psychologists in cross-cultural settings. Best known is the work of Jerome Bruner and Patricia Greenfield (3, 4). In studies among the Wolof of Senegal, Greenfield repeatedly found differences between village children with a few years of education and uneducated children on a variety of classification and Piagetian reasoning tasks. On a concept-formation problem, school children who were older and had attended school longer were more likely to form classes of items on the basis of form and function than were the younger school children, whereas the unschooled children showed no such difference with age, simply becoming more consistent in their use of color as a basis of classification. When presented with a standard Piagetian conservation task, children who attended school showed a developmental curve similar to that found in European and U.S. children, whereas the unschooled ones did not necessarily manifest conservation as they grew older. Greenfield summarized her results in the generalization that Wolof school children thought and performed more like Boston school children on these tasks than like their unschooled brothers and sisters.

A leading Soviet psychologist, Alexander R. Luria, found similar changes in concept formation associated with a change from informal to formal education among Central Asian peasants. His two contrasting groups were traditional, uncollectivized peasants living in small villages and peasant farmers who had moved onto collective farms. The latter generally had had a few years of schooling of some kind and were participating in the planning and management of large farm enterprises. In one study the subjects were shown four pictures, three being of members of a well-defined category and the fourth clearly not a member, and were asked to pick out the three that belonged together. One set of pictures, for example, depicted three tools—saw, ax, and shovel—and a piece of wood. Collectivized farmers commonly selected the three tools as the items belonging together, forming what Luria called an “abstract category.” Not one of the traditional farmers did so. Their choices were made on the basis of concrete, practical situations in which the various objects could be used together; thus the piece of wood, the saw, and the ax might be grouped because “it is necessary to fell the tree, then to cut it up, and the shovel does not relate to that, it is just needed in the garden” (5, p. 268). Luria also investigated the way in which the two groups went about solving verbal reasoning problems. When presented with logical syllogisms, the traditional people refused to accept the system of assumptions embodied in the problems and to draw conclusions from them, while slightly educated people readily drew such conclusions.

Educated Wolof children classified objects “on the basis of form and function” while unschooled children used “color as a basis of classification,” which aligns with what Luria found with the Uzbek villagers.

Neither approach is more “logical” — they represent different organizational principles. The striking finding is that “Wolof school children thought and performed more like Boston school children on these tasks than like their unschooled brothers and sisters.”

This suggests formal education creates specific cognitive habits that transcend cultural boundaries while severing connections to local knowledge systems. The “universality” of logical thinking may be merely the universality of a particular educational strategy.

IF this is so, then what we call “logical reasoning” might be better understood as a powerful but culturally specific cognitive tool. This tool may be sophisticated and useful, but it is neither universal nor basic to human thinking. If reasoning is indeed a learned technology rather than a universal cognitive capacity, then we face fundamental questions about education and epistemology.

Learning other modes of reasoning, I would argue, can allow us to see both the costs and benefits of our default approach. We might ask: What other reasoning modes have we deemed “illogical” that might actually serve important cognitive functions? Indigenous knowledge systems, intuitive decision-making, embodied cognition, and experiential wisdom may all offer cognitive resources that formal logic cannot provide. Rather than treating abstract reasoning as the gold standard of human thought, we might instead cultivate what I would call (channeling Thomas Kuhn’s last writings) cognitive bi-lingualism—the ability to move fluidly between different reasoning systems depending on context and purpose.

Status update

The Neither/Nor article remains in the same status as last week: “Your submission has passed the technical checks.”

I’m also excited to report I am typing on a laptop! But it’s not a Lenovo one, and it’s not new. It’s a refurbished Dell XPS 13 which I bought from Morgan Computers to tide me over. Luckily, the Clonezilla backup I took, plus about an hour of tweaking, got my whole Linux setup running on this laptop. The Dell is smaller and lighter than the Lenovo laptop, has a better screen, and a dramatically worse battery. But it is fine for now.

Here’s what Lenovo said yesterday, for those eagerly tracking the laptop which I sent them on 22nd April. This response came on Friday 23rd May after emailing them asking politely for an update on Tuesday 20th, Thursday 22nd, and Friday 23rd:

Dear Brayan ,

We apologies for the delay , i forwarded your email and question to the engineer and technician in charge in order to provide you the correct response .

I will be back to you as soon i receive feedback from them

Kind regards

<Name>Case Manager

Customer Care Team

Lenovo - EMEA Services Support

As always I’d love to hear from you,

Bryan

Thanks for this. I find Luria's transcripts so compelling.

You're not drawing the obvious conclusion. Ordinary people are using a more important and more basic form of reasoning.

Logic and maths are "rationalised" forms of reasoning.

They rationalised the world - a world of irregular bodies/forms behaving irregularly and somewhat unpredictably - and converted it by a giant feat of artificial imagination and absolutely not natural reasoning into artificial regular bodies [or more precisely symbols for bodies] behaving regularly and predictably. In logic: a world of units that behave in perfect chains of action and reaction, where q always follow p, and 1 + 1 always = 2 . Unlike the real world where 1 + 1 ice creams can soon equally one soggy mess.

What do we call this more basic form of reasoning? Realistics. Reasoning with real bodies. The world of vision and imaging/imagination (in the more general sense of "all forms of imaging"). Vision - visual reasoning - takes up something like 40% of the brain. Logic and maths were invented in part because they are vastly simpler computationally - but also more simplistic.

We have de facto passed from textual civilisation into multimedia civilisation - from book civilisation to multimedia screen - vision-based civilisation. The transcendence of logicomathematical (or symbolic) reasoning or "subscendence, by realistic-visual-real-body reasoning will be the result.